In-Depth

How did mountain lions become a bargaining chip in a political debate over Utah’s public lands?

by Emily Arntsen – 01.30.2024 – 20 min. read

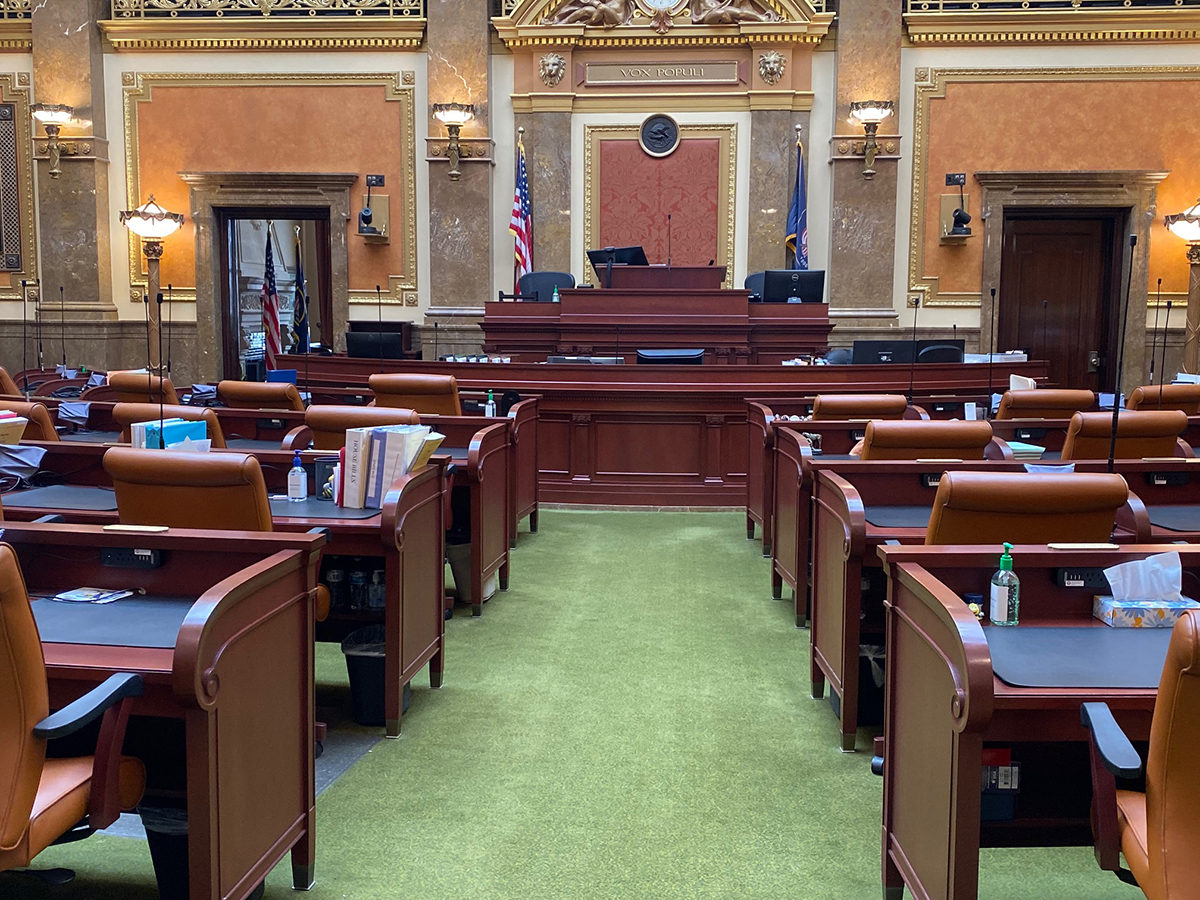

It’s been nearly a year since Utah lawmakers declared a no-holds-barred open season against mountain lions during the 2023 legislative session. The changes made to the state’s hunting laws kicked off a contentious and ongoing political battle that has provoked a lawsuit against the state and pitted some of Utah’s most influential subcultures against each other. Hunters, ranchers, conservationists, and even those concerned about the percentage of public land ownership in the state have found themselves fervently divided on the topic of cougar hunting.

A last-minute amendment proposed to House Bill 469 during last spring’s legislative session made cougar hunting laws as permissive as trout fishing regulations, with the idea that unrestrained hunting would knock down supposedly booming lion numbers.

“We’re getting an increase in our cougar numbers across the state,” said Scott Sandall, the Senate-side sponsor of the bill, during a floor discussion. No further debate followed.

The bill was signed into law by Gov. Spencer Cox on March 17 to the shock and horror of both conservationists and cougar hunters who were unaware of the changes made to the bill in the final days of the general session.

The new rules, which went into effect on May 3, extend the cougar hunting season from a few months to all year, allow trapping, and remove the harvest limit statewide and per person. Hunters no longer need specific mountain lion permits, which were previously awarded through a lottery system. Now, mountain lions are in the same licensing tier as trout, rabbits, geese, and other upland game species that can be hunted with just a basic combination fishing and hunting license.

State biologists were appalled by the changes. Their research shows that cougar numbers already are down and have been for the past seven years, empirical evidence that was spurned by politicians who claimed the exact opposite while proposing HB 469. But on the 43rd day of the 45-day legislative session, the facts touted on the Senate floor didn’t need to add up. Legislators just needed to say something that would strike the right chord with the cougar-hating “ag guys” who wield considerable lobbying power in Utah.

The Bait-and-Switch

Oddly enough, this story begins not with mountain lions, but with an entirely different though no less controversial debate — that of public versus private land ownership in Utah. From the outset, HB 469 proposed that $1 million per year be set aside for the state to purchase private lands for public hunting access and wildlife habitat restoration. The proposed “Wildlife Land and Water Acquisition Program” faced stiff opposition from those with a vested interest in preventing new public land ownership in a state where over 70 percent of all land is public.

“With the amount of public land in Utah, why do we need to purchase more land with tax dollars for wildlife? In our county, 77% is federal and 10% is state,” said Beaver County Commissioner Brandon Yardley during a debate regarding an early version of HB 469, a sentiment that was also echoed by other constituents. Lopsided public land ownership, according to this perspective, represents an imbalance of individual rights as well as a financial burden for struggling rural communities with very little taxable land.

Among the original opponents to HB 469 were the Utah Wool Growers Association and the Utah Farm Bureau, which said its official policy was to reject “the net loss of privately owned lands in the state.” In the end, some opponents couldn’t be swayed. But the Wool Growers Association was willing to make a deal, and the group promised to work with HB 469 sponsors “to find some common ground here.”

“Legislation is about compromise,” said Rep. Casey Snider, a Republican from Paradise and the bill’s main sponsor. “In order to reach an agreement, provisions were added.” So the wool growers, many of whom own large properties in northern Utah’s desirable hunting country, made a deal — open season on a predator that costs them thousands in losses each year in exchange for allocating tax dollars for the state’s acquisition of private land.

But what does the state stand to gain from this? Revenue, for one thing. Hunting is a big business in Utah, bringing in tens of millions of dollars each year. And for what it’s worth, as recently as 2022, Snider was the executive director of the Bear River Land Conservancy, an organization that creates conservation easements and partners with private landowners to manage properties and, in some cases, to allow public access for hunting.

Conservationists vs. The State of Utah

In October, two conservation groups — the Western Wildlife Conservancy and the Mountain Lion Foundation — filed a lawsuit against the state in the hopes of overturning HB 469. The lawsuit argues that with this new law, the state is violating its constitutional duty to manage wildlife for conservation and to preserve the opportunity for hunting and fishing for future generations.

“The constitution says that wildlife has to be governed by reasonable regulations to protect the future of hunting,” said Kirk Robinson of the Western Wildlife Conservancy. “How does HB 469 contribute to the conservation of mountain lions? It doesn’t impose any regulations at all.”

The lawsuit’s primary argument is that the right to hunt and fish, which was ratified by voters in 2020, requires active state management for the benefit of wildlife conservation. “In the absence of science-based, reasonable regulation of cougars, Utah risks extirpating or significantly reducing its population of cougars, in violation of the Utah Constitution, which requires that the State ‘forever preserve’ the right of the people to hunt and fish ‘for the public good,’” the lawsuit reasons.

The state responded to the lawsuit on Nov. 29 with a motion to dismiss the complaint, claiming that the law at issue is a political policy decision rather than a legal question.

In their Dec. 20 rebuttal, attorneys for the conservation groups wrote: “Certainly, the citizens of Utah who cast their ballots in favor of a new constitutional protection would be surprised to learn that the state considers an ‘individual right of the people’ to be an unenforceable one.”

No date has been set for the judge’s ruling on whether the case can continue toward trial, but the state as recently as Jan. 10 asked for a quick decision on the matter.

How Many is Too Many Mountain Lions?

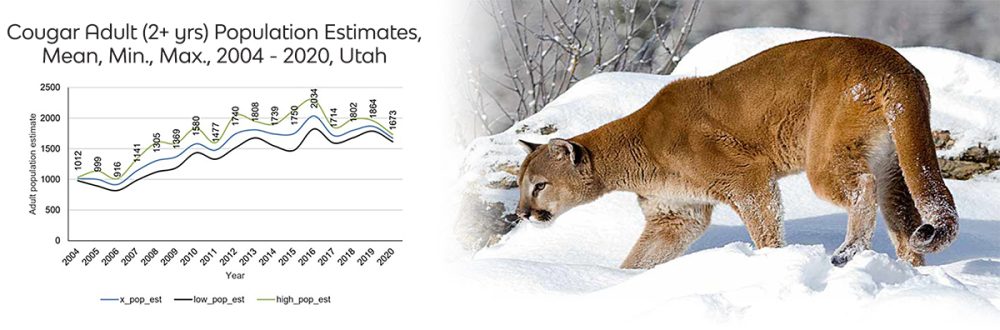

The general consensus among Utah biologists and others across the country is that mountain lion numbers are down.

“We have been seeing a decline in the cougar numbers overall,” said Darren DeBloois, a biologist who serves as the game mammal coordinator with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR). In Utah, the population peaked in 2016 with just over 2,034 mountain lions and has gradually dropped off. The most recent estimate from 2020 was 1,673 lions, according to DWR estimates.

The DWR assesses the state’s mountain lion population based on information from each year’s harvest. Every time a lion is killed by a hunter, the age of that lion is recorded and used to backfill a population model. For example, if 100 3-year-old lions were killed in Utah this year, the state knows that there were 100 2-year-old mountain lions last year and 100 yearlings the year before.

DeBloois acknowledged the system isn’t perfect. Because the data is retrospective, population estimates can only represent previous years. Right now, the model is three years behind. And since the population model is contingent on hunting, and because the number of hunting permits has changed each year depending on management goals, the population model is limited by how many permits are granted and how successful hunters are on any given year.

“The model is better for trends rather than raw numbers,” DeBloois said. “But there are still weaknesses. We’re assuming that people are harvesting cougars as they occur naturally in the wild, which isn’t true because hunters select for older males.”

Utah hunters killed 667 cougars in 2021, the most on record and the second back-to-back record harvest before falling precipitously to 467 in 2022. The number of state permits issued in recent years jumped to 4,144 in 2021, the most ever allowed and more than double the number just three years earlier. The number of permits sold dipped to 3,501 in 2022.

But numbers alone don’t tell the full story, according to Mark Elbroch, an ecologist and program director of Panthera, a mountain lion conservation group. Last year Elbroch published a study examining the best way to estimate cougar populations. In reality, “no one knows how many mountain lions there are,” he said.

Other states estimate cougar populations based on how hard it is to kill one, a metric referred to as “effort,” said Elbroch. “Effort could be how many people actually harvest or whether hunters even see a mountain lion,” he said. In some states, post-hunt surveys collect information on how hard it was to find or kill a lion, information that helps biologists come up with a population estimate. “Most people assume that more effort correlates to scarcity,” he said.

Of the methods Elbroch examined in his study, effort was the most accurate metric. But when it comes to wildlife management, accuracy is sometimes at odds with ulterior political goals. The discrepancies between methods can offer convenient alternative answers. “Depending on which metric you use, you can basically say whatever you want about the population,” he said.

None of the metrics is perfect. But if effort is the closest, then how hard is it to find mountain lions in Utah today compared to previous years? If the population is up, as some have claimed, hunting them should be easier.

“At least a third of the time I go out, I don’t even see one,” said Cody Webster, a lion hunter from Green River, Utah, who has been tracking cougars in the Book Cliffs his whole life. Webster also runs a guiding business called GT Outfitters, and about five years ago, he stopped offering cougar hunts. “When the management practices changed and we started seeing a decline in the numbers, we decided that we didn’t feel right contributing to that,” he said.

“Of course the population is subject to weather and different prey species, but it’s mostly affected by the management strategy,” Webster said, adding that he’s seen the correlation firsthand.

A female mountain lion and her three kittens. | Video Credit: Utah Mountain Lion Conservation

“A decade ago, we were catching two or three per day,” he said, explaining that during that time, the Book Cliffs awarded limited permits through a lottery system. “With a draw system, hunters feel like they need to be more selective with their harvest, only going for mature males.”

“It’s not just cougars. We’re seeing less of every species,” Webster continued. The cougar population benefits from higher deer and elk populations, which are down across the state. “Utah’s [old] management system was a lot more about preserving quality versus getting as many people out hunting as they can. There were less tags for everything.”

Utah’s Escalating War on Lions

Rep. Snider is quick to point out that even though the changes to lion hunting may seem drastic, he doesn’t believe they will have any serious effect on the population.

“Biologically, this is going to make zero difference because it’s almost impossible to be successful lion hunting without using hounds,” he said. Most people who hunt mountain lions use hounds to track down cougars and either tree the animal or corner it on a ledge without killing it. “For houndsmen, it’s more about the pursuit,” Snider said. “They police themselves pretty strictly, and they don’t take lions very often.”

Most houndsmen agree, with the caveat that “there are always a few bad apples,” according to Webster, who is also a board member of the Utah Houndsmen Association.

“If there’s no limit per person per year, someone could go out and trap whenever they want. That’s what worries me,” he said. “Especially with the trapping, I think the wool growers are going to be pretty hard on the numbers, especially in northern Utah.” Plus, he added, the new provisions could incentivize hunters to travel to Utah from other states, like Colorado, where hunting regulations are strict and an outright ban of all cougar hunting could be on the 2024 ballot.

“We have outfitters from Colorado that maybe don’t care as much because it’s not their backyard, not their mountain range, not their lions,” he said. “But it’s close enough that they can come and take advantage of it.” Since the season opened last fall, 367 mountain lions have already been killed in Colorado, spurring the state to call off the April hunting season.

For the past three years, the Legislature has required that the DWR cull — or facilitate culling through hunting — cougars, bears, coyotes, and bobcats whenever deer and elk numbers are below the state’s population goals, which has been the case for years. “Since HB 125 was signed into law, we’ve actually seen a decrease in the number of mountain lions in Utah,” says Denise Peterson, director of a nonprofit called the Utah Mountain Lion Conservation. “Over half of the units went into predator management status, which opened lions up to unlimited hunting.”

Utah’s escalating war against mountain lions is part of a larger trend throughout the West, Elbroch said, citing Idaho, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming as other states with similarly lenient lion hunting laws.

Idaho, for example, removed harvest limits for lions starting in 2021. “I’ve talked to houndsmen there who say cougars are now near impossible to find,” said Elbroch. “It would be one thing if Utah was an outlier. But when you’ve got neighboring states doing similar things, you’re going to see the population get knocked way down,” he said.

For the sake of argument, if Snider is right and his new law won’t bring cougar numbers down, how will wool growers benefit from the changes?

“This provision just makes it clear for wool growers that if they’re experiencing a depredation issue, they can take whatever actions necessary to address that,” Snider explained.

State law already allows wool growers to kill certain predators that are harassing or killing their livestock, but not by “whatever actions necessary.” Before these changes were made, ranchers were only allowed to hunt cougars that killed their livestock for 96 hours after the incident. And if they wanted to use snares — in other words, if they weren’t seasoned houndsmen — they first needed written permission from the state.

HB 469 does away with those restrictions on dealing with cougar depredation. So long as ranchers obtain a basic hunting license and comply with the state’s nearly non-existent regulations, they can track down and kill problem cougars however they want for as long as they want.

Scott Stubbs, a fifth-generation wool grower from Parowan, Utah, said he loses about 100 sheep to depredation each year in his flock of 3,000, causing about $25,000 in total losses. “In the past five years, we’ve had more depredation than in all my time,” he said.

Stubbs is in favor of the new bill. “Obviously, I’m in this business,” he said. But he acknowledged that when it comes to depredation, coyotes are “definitely my biggest problem,” not cougars.

Throughout Utah, coyotes are the number one cause of death among sheep and lambs, killing 8,800 (38.2 percent) in 2019, according to the most recent report from the United States Department of Agriculture. After coyotes, the next biggest cause of death was weather and poison, which accounted for 7,000 deaths (30.4 percent). The third biggest killer in 2019 was cougars with 3,000 deaths (13 percent), followed closely by bears at 2,800 deaths (12 percent).

Wool growers in Utah can receive reimbursements from the state for depredation incidents, but only if cougars or bears are the cause of death. Coyotes, eagles, ravens, dogs, and other animals that often prey on sheep are not covered by the state, says Leann Hunting of the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, which collects the “head tax” that’s used to reimburse ranchers.

Stubbs said the reimbursement amount varies depending on the market value of his sheep at the time, but he usually receives about $200 per sheep. In order for producers to collect reimbursements, a state agent must verify that the livestock was killed by a state-sanctioned predator. The carcass must be examined for certain characteristics — buried in the case of a cougar or belly-up in the case of a bear, Hunting explained.

Not all states require proof of predator when reporting depredation cases, though. And this can really skew the data to paint cougars as far deadlier than they really are, said Elbroch, who writes about depredation in his book, The Cougar Conundrum.

For example, the USDA’s most recent cattle death loss report states that mountain lions caused 42 percent of all cattle and calf deaths in Missouri in 2015. Another report from the USDA from the year prior claims that cougars killed 834 sheep in that state. What’s suspicious, Elbroch pointed out, is that “there are zero mountain lions in Missouri.”

The USDA aggregates data from state agencies, each with a different standard for collecting depredation numbers. In states where depredation reimbursements are only granted if certain predators, such as cougars, are culpable, then some ranchers might falsely claim depredation by cougars instead of coyotes if cases are self-reported, Elbroch said.

At the end of the day, though, it’s probably not worth splitting hairs over exactly how many cougars kill how many sheep because there is no evidence to suggest that culling cougars will decrease predation at all.

In fact, one study from 2016 found exactly the opposite — that cougar-livestock conflicts increased with an increase in hunting. Because trophy hunters target large males, a heavier harvest decreases the overall age of the population.

The study shows that when this happens, the cougar population becomes dominated by juveniles, which are less experienced hunters and more likely to wander into developed areas without territorial boundaries set by adults.

“They’re not good hunters. It’s hard to take down an elk,” said Robinson. “Instead they roam far and wide. They get into people’s yards. They kill the easy stuff — pets, sheep. [The wool growers] are shooting themselves in the foot.”

With Deer Numbers Down, How Can Utah Get More Bang for its Buck?

In this story, there’s one thing everyone can agree on: The mule deer population in Utah is not OK.

Consensus drops off quickly, though, when it comes to why mule deer have become so scarce. But buck hunters and wool growers, some of Utah’s loudest special interest groups, say that cougars, once again, are to blame.

From the state’s perspective, low deer numbers is a problem because the state makes a lot of money from hunting — hunting licenses brought in nearly $55 million in the 2023 fiscal year — and mule deer are the most popular big game animals in Utah.

In recent years, Utah’s mule deer numbers have been consistently below the “management objective,” a somewhat arbitrary population goal set by the state to ensure robust hunting experiences. This year, the DWR estimates that the mule deer population is 335,000, according to Dax Mangus, the big game coordinator for the DWR. That’s nearly 70,000 deer below the management objective.

“The biggest driving factors have been drought, followed by some heavy winters. This last winter, especially in northern Utah, was pretty impactful to mule deer,” said DeBloois, referring to the record snowfall in early 2023 that made forage scarce. In addition to weather, Utah’s current mule deer management plan also states that “loss and degradation of habitat are thought to be the main reasons for mule deer population declines in western North American over the last few decades.”

But the state can’t control the weather, and on the list of state priorities, urban development ranks higher than buck hunting. “It’s hard to stop urban expansion. It’s hard to stop vehicles from driving through areas where mule deer live. But it’s easy to say that if we kill more mountain lions, that should help the deer population,” said Peterson.

“Some people think it’s like one plus one equals two — cougars eat deer, and therefore, if we have less cougars, there will be more deer,” said DeBloois. “It’s not that simple.”

A recent study on deer-cougar relationships in Idaho, for example, found that “the benefits of predator removal are marginal” and “likely will not appreciably change long-term dynamics of mule deer.”

Peterson, who is originally from Michigan, said she’s seen how this kind of strategy can backfire. “I come from a state where we did wipe out all of the mountain lions, and I’ve seen the impacts of that lack of keystone species,” she said. “We don’t have a healthy predator guild that can regulate deer numbers. We have tons of dead deer on the sides of the highways. We have diseases like [Chronic Wasting Disease] that’ll wipe out entire herds.”

She points to the Kaibab Plateau deer fiasco of the early 1900s, a textbook example of a failed operation to boost deer numbers by eradicating predators. Hundreds of mountain lions and thousands of coyotes were killed in a span of about 30 years. During that time, the deer population swelled to nearly three times its size before crashing again as the boom led to overgrazing and mass starvation.

“It’s not unrealistic to say that could happen again,” Peterson said.

The Future of Lion Hunting Laws

While the fight over HB 469 plays out in court, there’s not much sign of movement in the political arena. DWR officials will evaluate the state of the cougar population after the first year under this new hunting law and take action accordingly.

Making adjustments to the law could be easier and just as effective as reversing the legislation entirely, DeBloois said. “If we have some concerns in areas where the numbers are getting low, we can restrict dogs, and that probably would be enough,” he said. Prohibiting the use of hounds during the winter, for example, would essentially outlaw lion hunting since successful lion hunts rely heavily on well-trained hounds and a good snow fall for them to track the lion’s scent.

So far, five wildlife-related bills have been filed in Utah’s 2024 legislative session, which began on Jan. 16. Another newly filed bill will address the cougar hunting law, but specific details are not yet available.

“I’m still trying to wrap my head around what mountain lion management should look like,” DeBloois said. “It’s a political question now.”

Republish

Republish Our Content

Corner Post's work is available under a Creative Commons License and under our guidelines:

- You are free to republish the text of this article both online and in print (Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence as in most cases we are not the copyright owner) but:

- you can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style and ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on Corner Post;

- if you’re republishing online, you have to link to us and include all of the links in the story;

- you can’t sell our material separately;

- it’s fine to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories;

- you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories to be republished individually;

- you have to credit us, ideally in the byline; we prefer “Author Name, Corner Post,” with a link to our homepage or the article; and

- you have to tag our work with an editor’s note, as in “This article was paid for, developed, and originally published by Corner Post. Corner Post is an independent, nonprofit news organization. See cornerpost.org for more.” Please, include a link to our site and our logo. Download our logo here.

Emily Arntsen moved to Moab, Utah, in 2020. She works as a reporter at Moab’s KZMU Radio and has written for other publications about the people, the history, and the ecology of the Colorado Plateau. Before moving west, Emily worked in Boston, Massachusetts, as a science writer and radio producer.

Emily Arntsen moved to Moab, Utah, in 2020. She works as a reporter at Moab’s KZMU Radio and has written for other publications about the people, the history, and the ecology of the Colorado Plateau. Before moving west, Emily worked in Boston, Massachusetts, as a science writer and radio producer.

Corner Post is a member of the Institute for Nonprofit News—a nationwide network of independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan news organizations. Learn more at

Corner Post is a member of the Institute for Nonprofit News—a nationwide network of independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan news organizations. Learn more at  Our stories may be republished online or in print under

Our stories may be republished online or in print under

6 thoughts on “How did mountain lions become a bargaining chip in a political debate over Utah’s public lands?”

I am sure glad there is people that realizes this open season is NOT right or fair to our lions. This is not fair to us Utah residents as out of state outfitters are coming here and slaughtering our lions & yes there is some “bad apple” resident outfitters doing the same thing!! This open season law is absolutely ridiculous cougars need to be properly manage but this open season is far from proper management. Cody is absolutely correct as this lion season has been the hardest season yet to go out and find lion tracks and has been on the decline for several years. I hope we can go back to a properly regulated season on our cougars!!!!

I strongly feel that cougar numbers are way down. I have hunted cougar for the last 15 years. I have never seen the hunting be this difficult before. I understand it is hunting and you will always had dry days, days where you will not find what ever you may be hunting. In this case a cougar. I went hunting in a 3 day period, We had three guys in three different trucks cutting around roads looking for a cougar crack. In three days three trucks can cover a lot of country in different mountain ranges. In those three days between all of us. One person looked at 1 old little female lion track. I think that alone should tell us that the numbers are down. It used to not be nearly as hard to find a cougar to chance l. I am one of the few guys that doesn’t kill a cougar because it is our hobby and there are plenty of other people that do not help the situation. It’s our sport and I hope we can figure something out to make it as fun as it could be and once was.

This open season is ridiculous, Lions need to be properly managed. Ten to fifteen years ago there were more elk more deer more lion more bear. Population was thriving in all aspects, the state needs to manage all units better and reduce the tags of every species and build up the animal population. Some of these big units in Utah have turned into a joke. The last several years the lion population has went down, with the prior management plans and now where it’s wide open the lion population is hurting. We need a respectable management plan. Build back up the lion population. Reduce tags in all species

Thanks Emily, Erica:

Well done! Certainly the best article I’ve seen on this sad topic.

Scott Berry

Utah has major issues with the political agenda and DWR management as well. When you have management and politicians looking out for only themselves and their pockets it’s a disaster. Deer management is not a money only objective as the DWR is now operating under. Leave politics out of game management, and reign in the DWR “underhanded, unethical policies” it currently utilizes.

There is no reason to have mountain lion hunting at all. California has proven that for 30+ years. They have far more mountain lion habitat than Utah does, and far more mountain lions, but hunting was outlawed in the early 1990s. There has not been an increase in human-lion conflicts since and the lion population has remained quite stable. If a particular lion becomes a problem by, for example, preying on pets or livestock, a “depredation” can be obtained from the state and that particular animal can be lethally removed. By this means, about 200 lions are removed from the CA lion population each year. The main problem with general hunting of mountain lions is that it is highly disruptive to the social structure of lion populations, which not only skews the population to younger animals but tends to lead to more conflicts with humans, including more bad human-lion interactions. And this assessment entirely leaves out any consideration of the interests of mountain lions or the role they play in maintaining healthy ungulate herds and ecological health. Most lion hunters, as you might guess, don’t care about these issues.

I am reminded of the skeptics who mocked and assailed Galileo when he claimed to have empirical evidence, obtained by meticulous observation, that Earth was not the center of the universe. They myth that Earth was the center of the universe defined their worldview and to assume it was false was to assume your entire worldview was false. The main purveyors of this view, the Roman Catholic Church, declared that what Galileo was saying was blasphemy and he was forced to recant and place under house arrest for the rest of his life. Old ideas often die hard, even when the evidence against them becomes overwhelming. In fact, this frequently causes a backlash in defense of the “official” doctrine.