Essay

Home

by Michael Collier – 4.28.2021 – 20 min. read

My father and I hiked into Grand Canyon in 1961. I still remember my keen disappointment half way down the Kaibab Trail, when he announced that we had nothing for lunch but sardines. Somehow, those meager rations got us down to Phantom Ranch. The ranch’s deep, cool swimming pool existed then, before a flood obliterated it five years later. In 1963, we traipsed into Havasu on Halloween and ate on the front steps of the village store—sardines again. Supai was spangled in black and orange bunting. Raven-haired kids rocketed by, laughing their horses into a frenzy. I was a wide-eyed thirteen-year-old alien, just in from a nearby planet called Phoenix.

The stratigraphy of my experience deepened layer by layer through the intervening half century—hitchhiking, bicycling, hiking to every corner of the Colorado Plateau, through the Rockies and out to the Pacific coast. I’m a child of the West. I’ve learned to orient myself by instinctively looking for Navajo Mountain, the Bears Ears, and, of course, the San Francisco Peaks. From a small plane, I’ve read this landscape like the lines on my hands. I’ve looked down and seen stories…there by Wildcat Butte, where I herded sheep for the Dandys. Or there on the Green River, where the black bear swam out to our boats. Or there in the Hobble Mountains, where I broke my neck cutting juniper. I observe this land from the vantage point of accumulated history.

The trajectory of that history has steadily evolved, veering now toward shoals I hadn’t anticipated. The West is different: more people, more roads, more noise. When my grandfather came out from Erie in 1963, I peered over the rim at Page where a dam was being built. Upstream along the quiet Colorado, there still lay an unspeakably beautiful canyon—Glen Canyon—where now there is only tepid water and a bathtub ring. Fields of sunflowers on the northern edge of Flagstaff have long since been bulldozed into subdivisions. Supai village where my father and I had walked—bunted and innocent—no longer exists in the way I once knew it. Now, the sky above the Navajo Reservation is often smudged downwind from powerplants, and the once-brilliant stars are dimmed by smog. Thirty years ago, I camped alone in Monument Valley where signs now say “No Hiking.” Today, bureaucracies stand arms-akimbo between me and the rivers I once ran. Cash-register rangers demand fees to walk upon lands that I thought were my birthright.

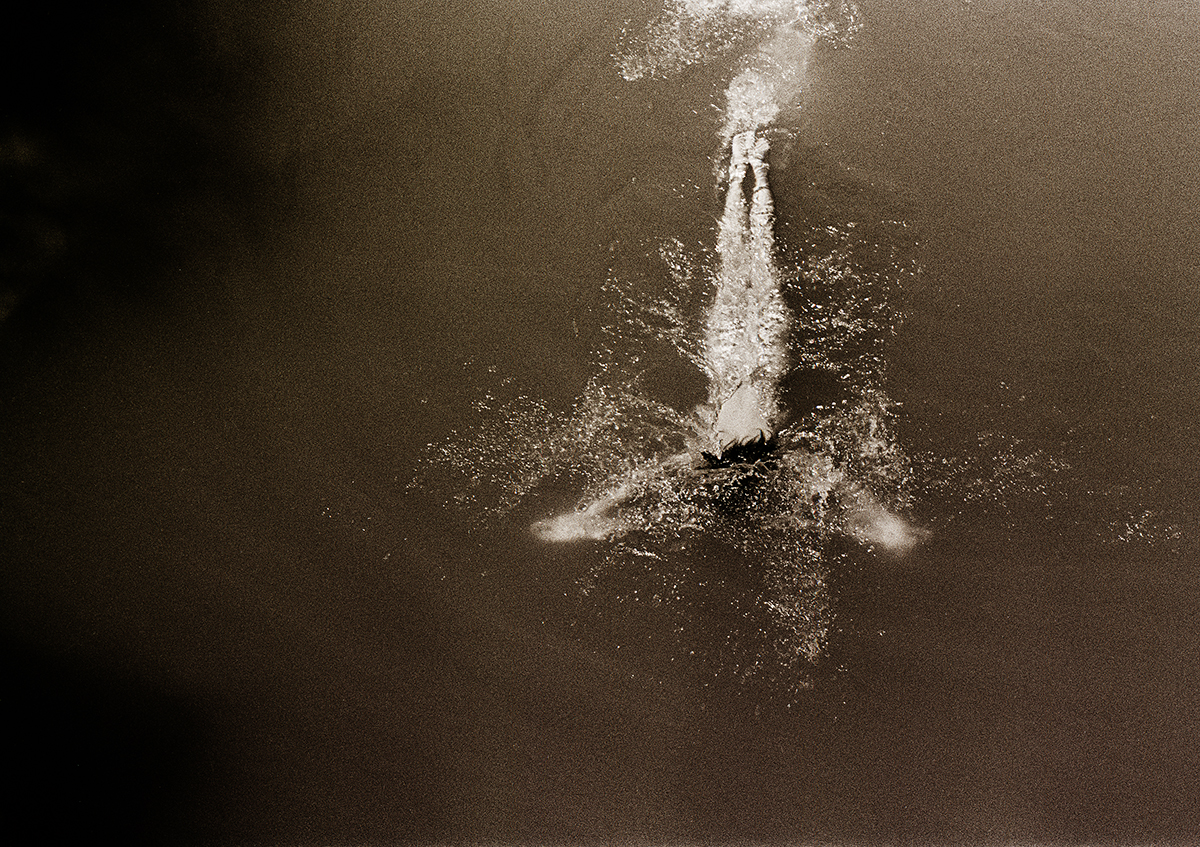

Is it possible to observe these changes without becoming discouraged or bitter? I sought to answer that question through the lens of my camera—the way I best relate to landscape. I set out across the Colorado Plateau, hoping to see my home with fresh eyes and an open mind.

What is it that draws people here? Red rocks and swallow-tailed canyons? The occasional blue-backed mountain? It’s certainly not the prospect of employment. For many, life on the Plateau turns out to be little more than poverty with a view. Arthritic joints would do at least as well in south Texas. Lawns grow greener in Connecticut, and the bass fishing is far better back in Blisterpack, Oklahoma. People don’t flee the rust-belt towns of Ohio or Pennsylvania or western New York for lack of family ties and tidy familiarity. Some come here out of curiosity. But others leave home because they’re searching for something more. People come here looking for hope— the hope of a new life, the chance to find a better place to raise children. The hope that springs from open space.

Newcomers arrive from the East, Midwest, and from California. They settle in Phoenix, then tire of that city’s ceaseless growth, and come to the Plateau hoping to resurrect a dim nostalgia for small-town peacefulness. When traveling, I cringe every time I hear somebody say that Flagstaff is cute, that Sedona’s red cliffs are mahvelous. Flagstaff expands by three percent every year, steadily gnawing at its surrounding forest. Along with Pinetop, Payson, and Prescott, we’ve become second-home handmaidens for the spill-over from Phoenix.

From its earliest days of logging and mining, the West has always bounced between boom and bust. The old trees have long since been cut. The bottom keeps falling out of the copper market but periodically gets welded back on. Water is exported to Los Angeles and San Diego like there is no tomorrow. Now, we’re exploiting our last great resource: open space. People move in and new housing developments fan out like sparks on the wind. We see these changes and resist. In darker moments, I worry that any effort at resistance is always doomed to fail, swimming upstream as it does against an incoming tide of humanity. We fight but give up ground acre by acre. Entire square miles are lost to the latest carpetbagger’s gated “community.”

The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was set aside in 1996. This part of southern Utah had been ranching country since the 1870s. The monument was established to protect almost two million acres from bulldozers and bad intentions. But how are fifth-generation ranchers who live and work within its boundaries supposed to abruptly adapt to a new way of life? Economies based on tourism require a continuous flux of new faces through towns like Bluff and Escalante that once were extremely isolated. Families can turn their farm houses into pretty little bed-and breakfasts, trading impoverished autonomy for the opportunity to smile and please. Some will adapt; others will resist until they are driven away.

Change on the Colorado Plateau is not just inevitable; it has already happened. The challenge is to live with change even while trying to manage it. The endless bickering between developers and preservationists is exhausting. That’s not an excuse to stop trying; it’s just an admission that conflict is tiring.

The sense of peacefulness I once found outdoors has been eroded. Too often when contemplating a pristine landscape, I see vulnerability rather than beauty. I’d love to say “OK, now everything is fine and I can live here in peace.” I can hold my breath, but that’s not likely to happen. I don’t like the idea of not welcoming a new neighbor, but neither do I look forward to being driven out of my home.

So, I wander through places like Grand Canyon, lugging my camera, shaking my head. Much has changed, but I can still bushwack my way to some of the beauty that remains. It’s a trick to see the land with fresh eyes; it’s so easy to remember how it used to be. Memories can be heavy baggage, the ruminations of an old man. How do I live in a changing landscape and still walk upright? When I rowed on the Colorado River for a living, I’d watch our passengers arrive at Lees Ferry, step off the bus and walk down to our boats. I felt jealous because they were about to see the Grand Canyon for the first time. These days I feel sad for those who arrive too late to see the Plateau I first loved. Perhaps, the newly-arrived are the lucky ones, though. For them—for you—there’s still a whole world to discover here.

Charles Darwin observed that, “It’s not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Architect Mary Jane Colter lamented, “There is such a thing as living too long.” She died a year later. At times, I can relate to what she said, but, usually, I seek a more viable solution. I look for a quiet place sheltered from these currents, a personal and private space.

For me, response to change will have to spring from the landscape itself. I had a dream once; perhaps, you’ve had one like it. I was standing beneath a cliff in Grand Canyon, looking up. Suddenly, a bus-sized boulder was hurtling straight down at me. In that dream-induced expansion of time, I lazily considered my options. I could try to spring aside in the remaining milliseconds and MAYBE, just maybe, get out of the way. Or I could stand there and see what would happen. I chose to watch. At the last fraction of a second, the boulder bounced off the cliff just above my head, flashed past, and vanished into the canyon below. I woke up, wondering what the dream meant.

The rock of overpopulation is hurtling down at us. I‘m naïve enough to hope it will bounce over our heads. I want, I need to be hopeful. Four of us hiked into Wet Beaver Creek in July, intent upon picking blackberries. A mile up the trail, we stumbled upon a young family swimming in the creek. They must have driven from Phoenix to escape the heat. The kids were hooting, splashing, and having the time of their lives. I apologized for barging in, but both parents insisted that we were welcome. “It’s not our pool. We’re happy to share it with you.” Their genuine good will was a ray of sunshine that reached deep into my heart. I should be so kind.

Our encounters with people on the Plateau occur against the backdrop of a larger human experience. We are all caught up in growth, maturation, and the passing of a precious torch —our love of a delicate landscape. I’ve learned much from Navajo shepherds and Mormon cowboys who surely saw me as a raw newcomer to a land they’ve known for generations. I hope I can live up to their legacy as I pass the torch on to others who have arrived yet more recently.

A few years back I flew two friends from Flagstaff to Lees Ferry. One sat up front, enjoying the flight and talking too much. The San Francisco Peaks, S.P. Crater, and Gray Mountain streamed by. I went into a daze, absently highlighting my passenger’s monologue with “hmmm”s and “uh-huh”s. The air was as smooth as the glassy lakes you once canoed at first light in your youth. We skimmed over the Marble Platform, five miles east of the Colorado River. Morning light washed up on Shinumo Altar, and poured like liquid gold over the rim into Marble Canyon. We glided above brown Navajo hogans and empty sheep pens. Every arroyo was etched in perfect detail as it tumbled toward the river.

My friend Fran Joseph sat in the back seat. This country is in her blood. She has hiked and boated here for decades, but had never seen it from this perspective. Fran hadn’t said a word over the intercom since we departed. I turned around to make sure she was okay. Tears were streaming down her face. “It’s so beautiful,” she said with a smile that looked like sunbeams between shafts of rain. “It is just so beautiful.”

Photography has been my guiding light for decades. It forces me to slow my pace and look around with a child’s eyes, with Fran’s eyes. Like every landscape photographer, I worry that I’m calling attention to quiet places even as I celebrate them. I fancy myself a catch-and-release photographer, but I know that we all leave our marks upon the land.

As a photographer and as a guide, I’ve introduced many people to the Colorado Plateau — in print and in person; from busses, planes, and boats. Marble Canyon is haunted by side canyons that perch above the Colorado River. The smooth white walls are treble clefs sculpted from Redwall Limestone. I first scrambled up to into those side canyons on a raft trip in the 1970s. The climb could be tricky; we’d set up ropes to protect passengers. Even so, one man slipped and broke his wrist. During the decades that followed, my hands and feet learned every finger and toe hold.

My river-running days slowed in the ‘90s. I returned in 1999 on a private river trip. I wanted to share Silver Grotto with a friend, but I stood baffled at the foot of its short cliff up from the river. I climbed a few feet and fumbled around, not finding the route. Then my extended right hand curled around a particular piece of unseen limestone — fist-sized, uniquely indented, intimately familiar even after the decades-long absence. I knew that piece of rock. At exactly that moment, I heard the soft voice of the landscape, telling me I still belonged. My friend followed me up into the grotto.

Home was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2004 issue of Plateau Journal, a publication of the Museum of Northern Arizona.

Republish

Republish Our Content

Corner Post's work is available under a Creative Commons License and under our guidelines:

- You are free to republish the text of this article both online and in print (Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence as in most cases we are not the copyright owner) but:

- you can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style and ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on Corner Post;

- if you’re republishing online, you have to link to us and include all of the links in the story;

- you can’t sell our material separately;

- it’s fine to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories;

- you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories to be republished individually;

- you have to credit us, ideally in the byline; we prefer “Author Name, Corner Post,” with a link to our homepage or the article; and

- you have to tag our work with an editor’s note, as in “Corner Post is an independent, nonprofit news organization. See cornerpost.org for more.” Please, include a link to our site and our logo. Download our logo here.

Michael Collier received his BS in geology at Northern Arizona University, MS in structural geology at Stanford, and MD from the University of Arizona.

Michael Collier received his BS in geology at Northern Arizona University, MS in structural geology at Stanford, and MD from the University of Arizona.

He rowed boats commercially in Grand Canyon in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s and then practiced family medicine in northern Arizona. Collier has published books about the geology of Grand Canyon, Death Valley, Denali, and Capitol Reef National Parks. He has done books on the Colorado River basin, glaciers of Alaska, climate change in Alaska, and a three-book series on American mountains, rivers, and coastlines. As a special projects writer with the USGS, he produced books about the San Andreas Fault, downstream effects of dams, and climate change.

Collier’s photography has been recognized by the USGS, NPS, American Geosciences Institute, and the National Science Teachers Association.

Corner Post is a member of the Institute for Nonprofit News—a nationwide network of independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan news organizations. Learn more at

Corner Post is a member of the Institute for Nonprofit News—a nationwide network of independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan news organizations. Learn more at  Our stories may be republished online or in print under

Our stories may be republished online or in print under