In-Depth

We Stole Land Again:

The Outdoor Industry, Indigenous Communities,

and

Bears Ears Conservation

by Amiee Maxwell – 6.2.2021 – 10 min. read

When Richard Gilbert bolted a new climbing route directly over an ancient petroglyph panel he mistook as graffiti in March 2021, the Access Fund, a national climbing advocacy group, used this as an opportunity to hold an online conversation about understanding and respecting Indigenous cultures. Conversations like this haven’t always been held so openly in the outdoor recreation community nor have they often included Indigenous voices. Recent conservation efforts to protect Bears Ears National Monument has thrust Indigenous voices to the forefront and the outdoor industry is learning to listen.

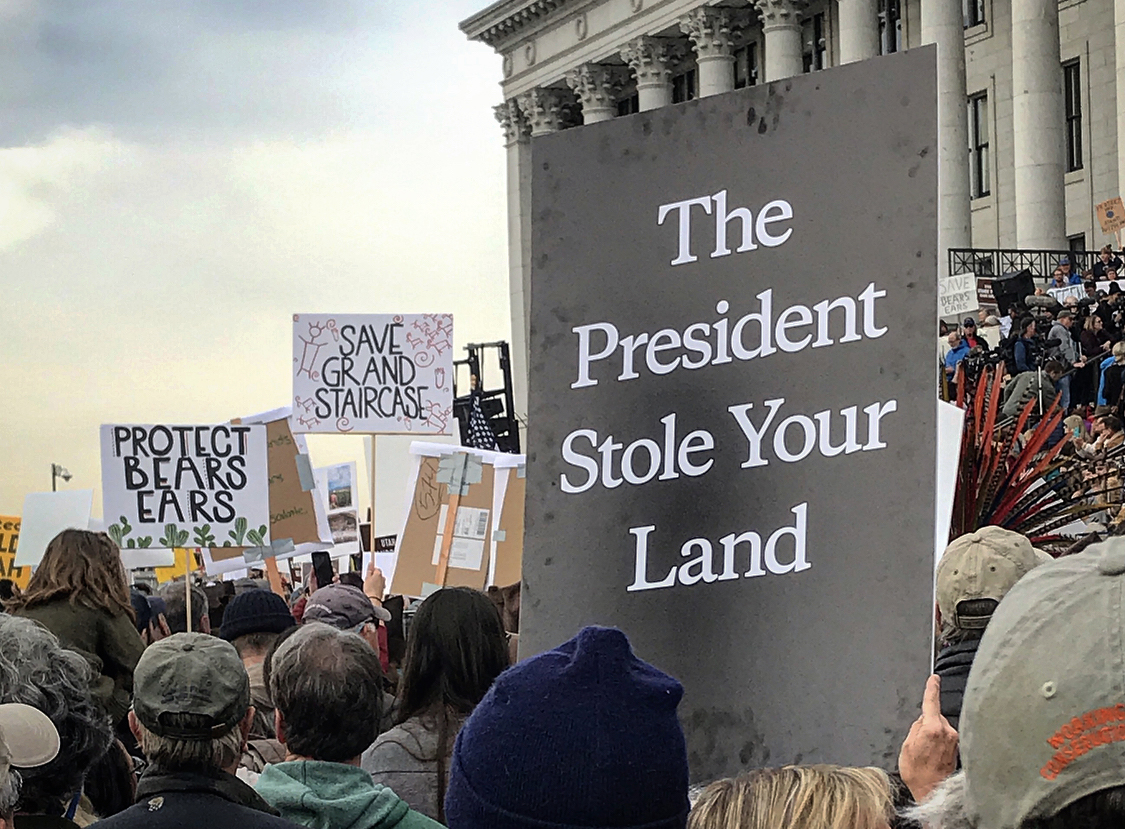

Four years ago when the Trump administration called for a review of over a dozen recently designated national monuments, the outdoor industry jumped into action. Rallies were held, letter-writing campaigns ensued, and the Outdoor Retailer trade show, the state’s largest convention of any kind, decided to leave Salt Lake City to protest Utah politicians’ push to reduce Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments.

Mere moments after Trump signed the formal proclamation dramatically shrinking the two Utah monuments on December 4, 2017, the outdoor apparel retailer, Patagonia, launched a particularly attention-grabbing campaign. Patagonia’s homepage went black with a stark message, “The President Stole Your Land.” Underneath the bold white letters read, “In an illegal move, the president just reduced the size of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments. This is the largest elimination of protected land in American History.” Three days later, Patagonia filed a lawsuit challenging this decision.

Named for the twin buttes that rise from the deep sandstone canyons, juniper forests, and high mesas of this region of the Colorado Plateau, Bears Ears is an area of immense cultural importance for five tribes: the Ute Mountain Ute, Uintah Ouray Ute, Diné (Navajo), Hopi, and Zuni. When Bears Ears was officially designated a national monument in December of 2016, it was the first successful Indigenous-led effort for a national monument in U.S. history.

The Bears Ears area is also home to Indian Creek, a world-class climbing destination known for its long, sandstone cracks—the kind of place van-living climbers dream of spending months at a time. Entire communities of climbers pop up on these lands each year and this is how many in the outdoor industry first got involved in Bears Ears conservation efforts, most notably, Patagonia.

“It was all about mobilizing the climbing community into greater activism to protect the place,” said Hans Cole, Patagonia’s Director of Campaigns and Advocacy, about the early days of Patagonia’s involvement in Bears Ears. It wasn’t until Cole made his first trip to Bears Ears in 2014 that it became apparent to him that the deeper story was the Native people’s connection to Bears Ears.

“We got really excited about the intersection of these two communities,” said Cole, “and thought the recreation community could add a voice.” Leading up to President Obama’s monument designation in 2016, Patagonia produced a film, Defined by the Line, designed to engage the climbing community in Bears Ears conservation efforts, and a multimedia piece that featured Indigenous voices. They also gave community-based grants to groups working on the ground in the area including Utah Diné Bikéyah, an Indigenous-led non-profit that works towards protecting culturally significant lands in the Four Corners region.

When Patagonia launched their “The President Stole Your Land” campaign they did so out of anger and outrage, said Cole, and also without Native input. “Our reaction reflected how much we cared about the place and our authentic emotion in the moment,” said Cole. Their messaging not only hit a nerve with members of the Trump Administration and local Utah politicians but also with Indigenous people and others actively involved in the conservation efforts

In fact, Utah Diné Bikéyah offers trainings for members of the media in appropriate coverage of Indigenous issues, and Patagonia’s “The President Stole Your Land” messaging has been referenced in these trainings as a specific example of problematic language. “These lands are Indigenous lands: Can you really steal ‘protected land’ already stolen?” read one slide during the training while another questioned if this really was the largest protected ‘land grab’ in American history.

Dr. April Anson is an Assistant Professor of Public Humanities at San Diego State University with a special interest in Indigenous studies. In a special issue of Western American Literature, she examined the use of Patagonia’s “The President Stole Your Land” messaging, noting the ad “whitewashes the bloody truth that North American history is written through the continuous theft of Indigenous lands, elimination through violence, broken treaties, and, often, in the name of ‘protection.’”

As part of her analysis, she offered a revision to Patagonia’s ad in a way that stressed decolonial thinking by replacing “The President Stole Your Land” with “The President Stole Land Again,” although this exercise was also without Native guidance. When she shared her rewrite with a group of Indigenous people, an Inupiaq woman suggested the ad should have simply read, “WE stole land again.”

Cole says if Patagonia had to do it over again, “We would pause and connect with our partners in the Native community first.” He says this experience has “definitely been a journey” and they still have a lot to learn. “We need to recognize that these are Native lands, that we are all visitors on them,” said Cole. “The history of them being stolen is absolutely real and we need to take our lead from the Native community.”

“This is what separates Patagonia from the rest of the herd,” said Angelo Baca, Cultural Resources Coordinator for Utah Diné Bikéyah and Diné (Navajo)-Hopi filmmaker. “They’re doing their best to figure out how to do better practices and how to implement them,” he said. In his view, Patagonia was willing to own up to its mistake in some regard and they never would have understood why “The President Stole Your Land” wasn’t the best approach had they not been willing to listen.

Baca expressed frustration that the outdoor industry and conservation community has taken so long to come back to the first community—the original people that have taken care of these lands since time immemorial. He believes it is the next step in conservation and the time is now given the current national context for social and environmental justice conversations. “Every institution needs to reevaluate diversity, equity, and inclusion, and conservation needs to do this first with Indigenous people,” said Baca.

Baca offers an analogy, “It’s as if everyone from the conservation community got into a vehicle and took off in one direction, and then all of a sudden they were lost. They didn’t know where they were going and then they finally noticed the empty seat beside them. ‘Maybe we should have gotten the Native people,’ they say. ‘They know the place, they know the plants.’ And now they have to turn all the way back to the beginning and pick us up and find the right way.”

Caroline Gleich, a professional skier and mountaineer, known for social media influence and activism among the outdoor recreation community, discovered how important it is for Indigenous representation in conservation issues early on in her Bears Ears involvement. While attending her first lobbying event on behalf of public lands in Washington, DC, she received some criticism that the outdoor industry groups she represented were making Bears Ears a climbing fight when supporting Indigenous leadership really needed to be the priority.

“At first I got really upset and defensive because it is hard to get feedback,” said Gleich, “but then I really learned about what it means for indigenous leaders to have a seat at the table in federal land management policy.” She describes this as a huge turning point for her activism and stresses how important it is to be able to take this kind of feedback. “We need to learn how to decenter our own stuff and see how powerful it is when we come together,” said Gleich.

Over 1,600 people registered for the Access Fund’s March 2021 “Discussion on Understanding and Respecting Indigenous Culture.” Panelists included Indigenous climbers from around the country as well as Richard Gilbert, the individual who admitted to bolting over the petroglyph panels himself. Coincidentally, on the day of the event, the words “White Power” were discovered etched into a beloved petroglyph panel near Moab, underscoring the urgency for these types of conversations.

The climbing and outdoor recreation community have to start making progress now,” said Chris Winter, executive director of the Access Fund, “Not only to prevent any more damage from being done but also to help the process of finding common ground and shared values.”

One panelist, Ashleigh Thompson, a member of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation and a Ph.D. Candidate in Anthropology at the University of Arizona, admitted she was apprehensive to join the discussion, given the Access Fund’s history of filing lawsuits against tribes to maintain access to climbing areas. “We appreciate so-called public lands because they allow us to access these areas to climb and recreate,” said Thompson, “Yet, one thing I’ve noticed in the climbing community and in the outdoor recreation community is ignorance of the history and contemporary significance of so-called public lands.”

Utah Diné Bikéyah’s Angelo Baca contributes to this discussion, adding that, “There’s a lot of privilege and a lot of imposition from these folks who are enjoying public lands or national monuments or parks, and almost never give a second thought that they are only public because they were stolen.”

To recreate respectfully and responsibly on Indigenous lands, Thompson suggests that knowing whose land you’re on, using Indigenous place names, investigating local Tribal protocols, practicing good stewardship, and supporting Indigenous activism are all good places to start.

A common theme throughout these discussions is the idea that access to lands such as Bears Ears provides opportunities for healing. While mistakes have been made—and likely will continue to be made—how the outdoor recreation and conservation communities hold themselves accountable and how they choose to listen and learn from Indigenous voices moving forward will help determine how these communities collectively heal.

“The Indigenous people and the land see themselves as relatives, as connected, they’re one. So if you don’t recognize the land, you don’t see me. If you don’t see me, you don’t see the land,” said Baca. “That’s the thing that I think people have to walk away with today is to understand that this conversation is way deeper than just somebody bolting in a rock panel. We’ve only just started this conversation.”

Republish

Republish Our Content

Corner Post's work is available under a Creative Commons License and under our guidelines:

- You are free to republish the text of this article both online and in print (Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence as in most cases we are not the copyright owner) but:

- you can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style and ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on Corner Post;

- if you’re republishing online, you have to link to us and include all of the links in the story;

- you can’t sell our material separately;

- it’s fine to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories;

- you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories to be republished individually;

- you have to credit us, ideally in the byline; we prefer “Author Name, Corner Post,” with a link to our homepage or the article; and

- you have to tag our work with an editor’s note, as in “Corner Post is an independent, nonprofit news organization. See cornerpost.org for more.” Please, include a link to our site and our logo. Download our logo here.

Amiee Maxwell reports on local government and community happenings for The Wayne & Garfield County Insider. She’s also a frequent contributor to Atlas Obscura and Utah Stories Magazine. Originally from the Midwest, she now calls Torrey, Utah her home.

Amiee Maxwell reports on local government and community happenings for The Wayne & Garfield County Insider. She’s also a frequent contributor to Atlas Obscura and Utah Stories Magazine. Originally from the Midwest, she now calls Torrey, Utah her home.