Essay

The Shape of the Land

An Architecture of Place

by Christa Sadler – 3.24.2021 – 25 min. read

As a child, when I was beginning to learn geography, my parents would take me traveling around the Southwest for dances at the Hopi Mesas and the pueblos of the Rio Grande, for Christmas at Taos Pueblo and Thanksgiving by mule at Phantom Ranch. As we traveled across the wide landscapes, my head filled with the images and sensations of mesa, butte, cliff, cuesta, hogback, badland, canyon, peak, and plateau. When I came back to live among the images of my youth, the Colorado Plateau was a beacon, drawing me away from the sprawling coastal cities and green-gold hills of California.

As I began running rivers, photographing, geologizing, and roaming the Plateau lands to appease my wanderlust, it didn’t take long to realize that the Colorado Plateau is far more than I had ever imagined as a tired young traveler in the back of the station wagon. It is a landscape of contrasts in color, shape, light, sound, elevation, vegetation, and geology—truly more than just the sum of its parts. I have never been one of those people who spend much time wishing I were a bird, but in this region, I often wish for natural wings to soar over the rolling tapestry below me.

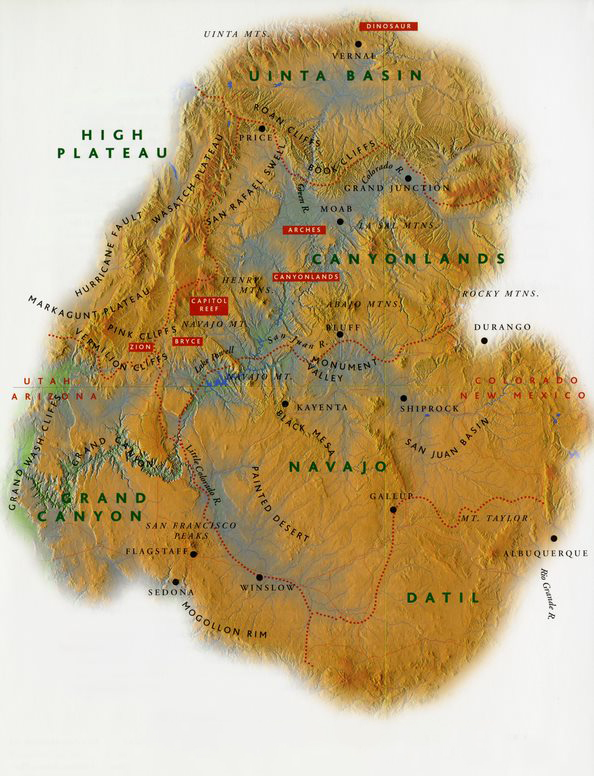

The Colorado Plateau comprises the territory known as the Four Corners, where the states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah join borders. The region encompasses 130,000 square miles, a greater area than that of New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania combined. It is indeed a highland, with an average elevation of 5,000 feet—some portions of the region reach 11,000 feet above sea level. In geologic structure, the Plateau is shaped something like a saucer, slightly higher around the edges. This saucer is gently tilted down to the northeast. This doesn’t mean that the northeast Plateau is necessarily lowest in topographic elevation, only that its underlying structure, formed millions of years before the region actually became a plateau, tilts in that direction.

To illustrate this, we can use for a marker the Kaibab Formation, that creamy pale limestone that forms the surface of the land surrounding the Grand Canyon and Flagstaff. On the southern boundary of the Plateau this layer lies 7,000 feet above sea level. At Lees Ferry, 120 miles to the north, the limestone lies at only 3,000 feet in elevation. And if one could find the Kaibab Formation in the northern part of the Plateau, it would be more than a mile below sea level. On top of this tilted foundation, the fingers of deposition, erosion, and crustal movements have played across the land for millions of years, shaping it like a stern and loving sculptor.

Geologically, the Colorado Plateau is an island of relative stability surrounded by a sea of chaos. To the north and northeast lie the rumpled and uplifted Rocky Mountains and to the west, south, and east the land has been torn apart, stretched and faulted into the deep basins and tilted mountains of the Basin and Range. Even the Rio Grande River valley is an incomplete tear in the earth’s crust. By contrast, the Plateau is characterized by relatively flat-lying and undisturbed sedimentary rock layers topped only, like the words on a birthday cake, by small uplifts and downwarps, furrows in an otherwise relatively unruffled cloth.

Here, it is best to have wings…

Here, it is best to have wings, as it is not always easy from the ground to recognize that one has entered the geographic and physiographic entity that maps label as the Colorado Plateau. Fly like a hawk to the south, towards the red rocks of Sedona and Sycamore Canyon, and swoop over the Mogollon Rim, which forms the prominent southern boundary of the Plateau. Here the rim easily evokes The Edge: a rugged escarpment over 2,000 feet high, scored with hundreds of small drainages, tree-lined canyons, and streams flowing out to the Verde Valley.

Veer southeast on the winds that buffet the rim, and the edge of the Colorado Plateau becomes less well defined. The green forests of the Mogollon tumble like a wrinkled carpet off the Plateau towards the lowlands to the south, but even your hawk’s eyes will have trouble following the rim as it softens into New Mexico, fading into a nebulous mountainous region. As you bank to the north, you follow the wide gash of the Rio Grande River valley, just off the eastern edge of the Plateau.

Flying north up the river, past the tumbled earthen blocks of the pueblo towns among their green fields, your path takes you towards the high peaks of the southern Rocky Mountains. The San Juan Mountains of southwest Colorado lie just beyond this corner of the Plateau. In Colorado, the boundary between the Plateau and the Rocky Mountains is often marked by the Grand Hogback. This scalloped frill of upturned rock layers stretches up beyond Grand Junction and the Book and Roan Cliffs, marking the western edge of the uplifted Rocky Mountains.

Fly the Hogback north and catch an updraft from the Uinta Mountains as they rise just outside of Vernal, Utah. This east-west mountain range forms the Plateau’s northern boundary. Then veer west again towards the sun and the Wasatch Range, down along the sinuous trace of the Hurricane Fault, running south through central Utah to the northwest corner of Arizona at Lake Mead and the Grand Wash Cliffs. At the bright blue waters of Lake Mead, the sharp escarpment of the Grand Wash Cliffs marks the end of the Grand Canyon, the edge of the Colorado Plateau, and the beginning of the open western deserts.

The Colorado Plateaus

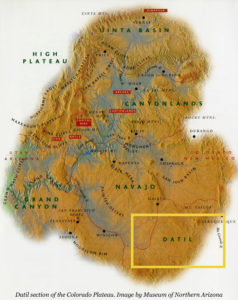

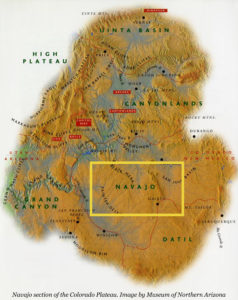

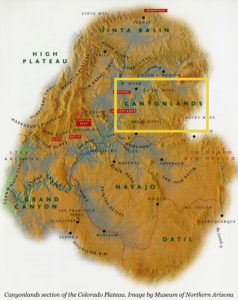

We have flown the boundaries of the Plateau, but this tells us little about the diversity of geology, landscape, landform, color, and texture that lies within the borders of the map we have drawn. Although the region is currently referred to in the singular, it used to be referred to as the Colorado Plateaus, being composed of several regions sharing similarities, but different enough from each other to be truly distinct. Geographers have often divided the Colorado Plateau into six “sections,” each with its own unique characteristics. Travel to any one of these regions will leave vastly different impressions on the visitor. Upon these disparate landscapes a variety of ecosystems and peoples have created tapestries as diverse as their surroundings.

Grand Canyon Section

Taking to the air again, we fly first over the Grand Canyon section, in the southwestern portion of the Colorado Plateau. This is a landscape of high grasslands, cinder cones, and lava flows, but it is named for its preeminent landform. The great chasm exemplifies the geology and geography of the area: complexly folded and faulted Precambrian rocks overlain by about 4,000 feet of essentially undeformed Paleozoic sediments, 510 to 220 million years old.

From the air, it is easy to see that these upwarps have gently inclined flanks to the west and bend steeply to the east in a single fold called the monocline.

This section is also characterized by asymmetrical bulges in the earth’s crust. From the air, it is easy to see that each upwarp has a gently-inclined flank to the west and bends steeply to the east in a single fold called a monocline. The main portion of the Grand Canyon has been carved through the bulge of the Kaibab Upwarp. Gazing northward from the Desert View Watchtower on the South Rim of the Canyon, we can see the obvious welt in the crust, flanked with the sharp fold of the East Kaibab Monocline, fading east towards the Painted Desert. Farther north into Utah, the ragged line of rock layers eroded out of this fold is known as the Cockscomb. Geologists are still arguing, 150 years after they first asked the question, about how the Colorado River carved through this fold and into what are now the highlands of the Kaibab Upwarp.

This section is also characterized by asymmetrical bulges in the earth’s crust. From the air, it is easy to see that each upwarp has a gently-inclined flank to the west and bends steeply to the east in a single fold called a monocline. The main portion of the Grand Canyon has been carved through the bulge of the Kaibab Upwarp. Gazing northward from the Desert View Watchtower on the South Rim of the Canyon, we can see the obvious welt in the crust, flanked with the sharp fold of the East Kaibab Monocline, fading east towards the Painted Desert. Farther north into Utah, the ragged line of rock layers eroded out of this fold is known as the Cockscomb. Geologists are still arguing, 150 years after they first asked the question, about how the Colorado River carved through this fold and into what are now the highlands of the Kaibab Upwarp.

To the south and west of Grand Canyon Village, volcanic rocks spill onto the land and decorate its surface as cinder cones and other volcanoes. Perhaps a third of the Grand Canyon section is covered by volcanic rocks belched out between 8 million and 1,000 years ago. The San Francisco Peaks and Sunset Crater near Flagstaff, Arizona, crown an extensive volcanic field formed during this period, as do Vulcan’s Throne and the lava flows of the Toroweap area in western Grand Canyon. These volcanic rocks lie directly on top of the older Paleozoic sediments, the remnants of seas, rivers, and dunes hundreds of millions of years old. Thousands of feet of younger rocks found elsewhere on the Plateau were stripped away here in a massive episode of erosion before the volcanoes erupted and fissures spilled forth their lava flows.

From a distance, the San Francisco Peaks and the volcanic field’s cinder cones float on the horizon like mirages. For the Diné and Hopi nations, these islands rising from the desert floor mark the boundaries of the sacred. This is the West Mountain of the Diné and home of the Hopi Katsinas—source of pine and fir boughs used in ceremony and source of the summer rains that mature the crops. When the Katsinas return home to the Peaks at the end of July, they do so laden with the people’s prayers for rain. Standing on the grasslands and watching the cloud-wreathed Peaks before a summer storm, it is not hard to imagine the ancestors gathering to bring rain to the deserts.

Datil Section

Fly now to the east, towards the New Mexico border. Cross the grasslands south of Winslow, Arizona, in the valley of the Little Colorado River far below you, and towards the Datil section. The land here is also covered by thick lavas, many of which erupted within the last 10,000 years from Mount Taylor near Grants, New Mexico. All that remains of once extensive gooey masses of lava are isolated black and twisted flows, the tire- and shoe sole-eating malpais (“bad country”) of early Spanish travelers to the region. Lava-capped mesas in western New Mexico are remnants of low places into which the lava flowed. Protected from erosion by their caps of hardened lava, these once low places were more resilient and now stand high over their surroundings, in a textbook example of what is known as “inverted topography.”

Mexico border. Cross the grasslands south of Winslow, Arizona, in the valley of the Little Colorado River far below you, and towards the Datil section. The land here is also covered by thick lavas, many of which erupted within the last 10,000 years from Mount Taylor near Grants, New Mexico. All that remains of once extensive gooey masses of lava are isolated black and twisted flows, the tire- and shoe sole-eating malpais (“bad country”) of early Spanish travelers to the region. Lava-capped mesas in western New Mexico are remnants of low places into which the lava flowed. Protected from erosion by their caps of hardened lava, these once low places were more resilient and now stand high over their surroundings, in a textbook example of what is known as “inverted topography.”

Here we are in a land of Diné legends. Mount Taylor is the Sacred Peak of the South, fastened to the earth with a great stone knife and decorated with turquoise, dark mist, and female rain. And long ago, in a time when monsters terrorized the Diné ancestors, twin heroes of divine descent were tested to manhood by killing off every monster they could find. The lava flows of western New Mexico are said to be the dried blood of one of these monsters, spilled over the land in its death throes.

Navajo Section

Navajo Section

Turning on the winds back to the north, we reach the Navajo section. This is a structural low point on the Plateau, where the land was warped downwards many millions of years ago into a deep basin filled over the millennia with sediments from lakes and rivers. The deepest part of this depression is the San Juan Basin in northwestern New Mexico. The same layer of rock that forms the land surface in the Grand Canyon Section lies over two miles down in the center of the San Juan Basin, buried by about 10,000 feet of later Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments. Here are the mysterious Bisti Badlands, painted sediments from the Age of Dinosaurs that have eroded into strange and whimsical shapes, where few plants grow on the low shale hills to break the fierce grip of the wind. Oil and natural gas wells sprout from the land’s surface to suck deep into ancient reservoirs formed millions of years ago in the ever deepening pile of sand and mud accumulating in the basin’s depths.

We fly over the Defiance Upwarp, into which Canyon de Chelly’s pale sandstone walls have been carved. This high bulge separates the San Juan Basin from the Black Mesa Basin to the west. Black Mesa rises in defiance of erosion, composed of ancient sea and shoreline sediments preserved as a massive plateau, the core of which hides the coal deposits that formed as plants along the shores of this ancient seaway lived, died, and accumulated in a thick pile. At the foot of Black Mesa lie the rumpled badlands of northern Arizona’s Painted Desert, spread out below our wings in a pastel carpet; remains of an ancient “Mississippi” that flowed west from Texas to the coastline in Nevada over 200 million years ago. The earth’s earliest dinosaurs wandered these lands, foreshadowing more than 150 million years of ecological dominance.

This is the land John Ford made famous, what the magazines call “Indian County”—a land of endless red rock horizons filled with mesas, buttes, and monuments…

The Navajo section is a landscape studded with volcanic necks such as Agathla Peak in Monument Valley and Shiprock in New Mexico. The topography extends uninterrupted for miles: broad swaths of soft shale separated by low ridges of sandstone, on through the southernmost portion of Monument Valley. This is the land John Ford made famous, what the magazines call “Indian Country”—a land of endless red rock horizons filled with mesas, buttes, and monuments that beg to be named after stagecoaches, eagles, mittens, bears, and rabbits.

Canyonlands Section

Turning north from the Na vajo section, we soar high over the colorful heart of the Colorado Plateau: the Canyonlands section. No other name could be so accurate—hundreds of canyons carved by streams both ephemeral and perennial coil through this wrinkled country. From the air we can see them, curling and branching like sinuous tree limbs, intent upon the sea many thousands of feet below. It has been estimated that if one could stretch this landscape to remove all the “wrinkles” on its surface, it would reach two thirds of the way across the United States. In large part because of these canyons, this remained the least known and last explored (by white travelers) portion of the western United States—until the mid-1800’s, the maps showed a huge blank spot here labeled simply as “Terra Incognita.”

vajo section, we soar high over the colorful heart of the Colorado Plateau: the Canyonlands section. No other name could be so accurate—hundreds of canyons carved by streams both ephemeral and perennial coil through this wrinkled country. From the air we can see them, curling and branching like sinuous tree limbs, intent upon the sea many thousands of feet below. It has been estimated that if one could stretch this landscape to remove all the “wrinkles” on its surface, it would reach two thirds of the way across the United States. In large part because of these canyons, this remained the least known and last explored (by white travelers) portion of the western United States—until the mid-1800’s, the maps showed a huge blank spot here labeled simply as “Terra Incognita.”

The waters of the Green, Colorado, and San Juan Rivers and their tributaries have eroded gorges that rival the Grand Canyon in beauty and extent. They have conspired to create a landscape of leftovers and remnants—of monuments, spires, alcoves, arches, bridges, and buttes. This is a land that challenges the imagination to see what is no longer there.

Mormon pioneers faced challenges of a far different nature in this landscape. Even the smallest of the incised waterways in the Canyonlands section provided obstacles to the wagons, horses, and oxen of the 1879 “Hole in the Rock” party sent east to settle the lands along the San Juan River in the far reaches of the Mormon panorama. A proposed shortcut across the canyon of the Colorado River in Glen Canyon turned into one of the greatest engineering feats in the region’s early history. Roads were literally blasted out of sheer cliffs, log and rock “dugways” patched against the sandstone, and wagons and their teams belayed down more than one of these perilous crossings. A six-week journey lasted six months instead, due largely to this discouraging geography. At the top of their final ascent up Comb Ridge along the San Juan River, one weary traveler stopped to carve into the sandstone cliff the words, “We thank thee oh God.” It takes little effort, when gazing from our aerial perspective over this corrugated land, to imagine the weariness and discouragement felt by pioneers who may have had little appreciation for the beauty surrounding them.

The kaleidoscopic rocks of the Canyonlands section are from the later Paleozoic and Mesozoic Eras, between about 320 and 75 million years old. The red sandstones and shales of Monument Valley and Canyonlands are sediments washed down from the highlands of an ancient mountain range to the east. Here, sail-finned reptiles and lumbering amphibians wandered ancient rivers and deltas during the Permian Period, 280 million years ago. The massive luminous walls of Navajo Sandstone at Capitol Reef National Park and in Glen Canyon preserve dunes across which dinosaurs walked. The austere gray badlands of the Mancos/Tropic Shale near Grand Junction, Colorado, Mesa Verde National Park, and Capitol Reef settled in the waters of the last seaway to cover this land—a Late Cretaceous home to sharks, ammonites, and flippered marine reptiles.

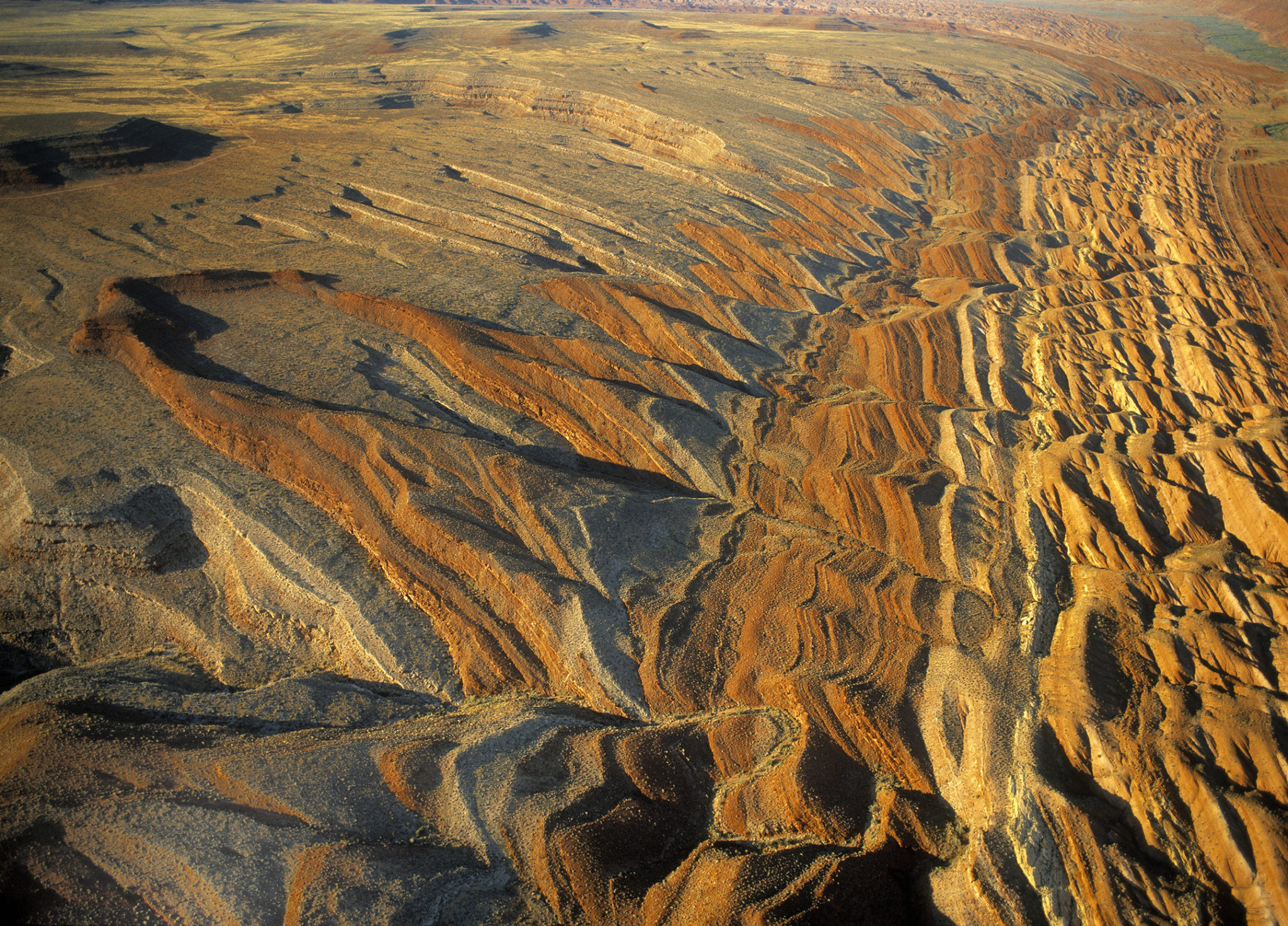

Several large upwarps separated by deep basins rumple the surface of the Canyonlands section. While the central portions of these upwarps long ago yielded to the patient hand of erosion, their flanks are armored with flatiron ridges of resistant rock, eroding like a rind from the tops of the high points. Birds wheel and soar over these “reefs,” so named because early travelers crossing the region likened them to the treacherous oceanic reefs of early sailing days. These reefs were often just as difficult to cross for groups laden with wagons and stock. Capitol Reef draws its name from such a structure on the northern end of the Waterpocket Fold, one of the finest examples of such an eroding flexure in the world. Comb Ridge similarly forms the eastern edge of the Monument Upwarp, into which Monument Valley eroded.

Birds wheel and soar over these “reefs,” so named because early travelers crossing the region likened them to the treacherous oceanic reefs of early sailing days.

Several mountains of unusual origin rise across the Canyonlands section. The La Sals, Henrys, Abajos, and Navajo Mountain all formed when magma from within the earth bulged the overlying sediments upward into a dome in an attempt to burst onto the surface. In most cases, the sediments on top of the dome have eroded, exposing hard igneous rock at the core.

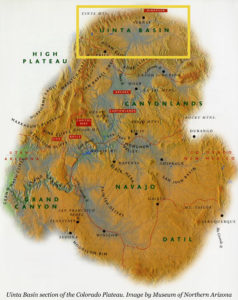

Uinta Basin Section

As we fly north into the valley where the Colorado and the Gunnison Rivers join, a line of cliffs appears on the northern horizon. The 2000-foot wall of the Book Cliffs bounds the Uinta Basin section, standing vigil over Canyonlands to the south.

Although it’s hard to tell from the air, the Uinta Basin is structurally the lowest point on the Plateau. Here, the same rock that lies two miles below the surface in the San Juan Basin is as much as four miles below the main street of Vernal, Utah. This is due not only to the general tilt of the Plateau, but also to the downward flexure that created the basin 70 million years ago. Sediments from the Age of Mammals form broad hilly benches that slope to the north; their southern end erodes to form the south-facing Roan and Book Cliffs, marching north to the edge of the Plateau.

The Uinta Basin is strangely lovely—a wil d, open, and often harsh landscape. In the spring, winds blow mercilessly and mosquitoes torment anyone near a water source. In the summer the baking heat sears anything silly enough to be out in the mid-day sun, and in the fall the creeks and rivers are lined with golden cottonwoods, and thousands of Canada geese and sandhill cranes gather at the basin’s waters. Winter temperatures fall sharply and watercourses freeze. Early Mormon explorers to the area were less than impressed with the landscape. They returned a report to Salt Lake City that described the area as, “One vast contiguity of waste and measurably valueless except for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians, and to hold the world together.” Although Brigham Young convinced the Ute Indians near Salt Lake City to move there because no white settler wanted it, ranchers began to eye the land in the late 1870’s and brought their cattle to graze along the banks of the Green, White, and Uinta Rivers. While this tactic didn’t yield great riches for either Ute or Mormon, their measurably valueless land has since produced substantial quantities of oil and uranium.

d, open, and often harsh landscape. In the spring, winds blow mercilessly and mosquitoes torment anyone near a water source. In the summer the baking heat sears anything silly enough to be out in the mid-day sun, and in the fall the creeks and rivers are lined with golden cottonwoods, and thousands of Canada geese and sandhill cranes gather at the basin’s waters. Winter temperatures fall sharply and watercourses freeze. Early Mormon explorers to the area were less than impressed with the landscape. They returned a report to Salt Lake City that described the area as, “One vast contiguity of waste and measurably valueless except for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians, and to hold the world together.” Although Brigham Young convinced the Ute Indians near Salt Lake City to move there because no white settler wanted it, ranchers began to eye the land in the late 1870’s and brought their cattle to graze along the banks of the Green, White, and Uinta Rivers. While this tactic didn’t yield great riches for either Ute or Mormon, their measurably valueless land has since produced substantial quantities of oil and uranium.

At the basin’s northern extreme, the sharply uplifted spine of the Uinta Mountains veers to the sky as the gateway to the Rocky Mountains and Dinosaur National Monument nestles snugly into its southern flank. The Green River exits the mountains and meanders lazily across the pale red and brown badlands. The river here is a calm contrast to the confining walls and rocky falls of the canyons of Lodore and Split Mountain. John Wesley Powell’s 1869 expedition down the Green River had already lost one of four boats by this point in their journey. After the wreck of one boat and the loss of a third of their provisions, Powell became even more dedicated to portaging and lining boats through any rapids they could, a program that didn’t sit well after a time with his men. Despite the distaste for wrecking boats, or carrying gear and lining heavy boats in swift current, however, some of the men preferred swift water to the meandering path of the Green River through the Uinta Basin. George Bradley wrote here in his journal that, “We have had a hard day’s work. Have run 63 miles and as the tide is not rapid we have to row a little which comes harder to us than running rappids (sic).” He also mentions mosquitoes.

We soar down the river as it follows its course southward. The badlands, benches, and cliffs over which we fly are rare (for the Colorado Plateau) remnants from the beginning of the Age of Mammals, rich enough in early mammal remains that entire North American fossil faunas are named for them. These sediments formed in the massive, ancient Green River Lakes and the streams feeding them. They preserve an extraordinary array of fossils, including fish, bird tracks, turtles, early primates, insects, leaves, and feathers.

Paleontological research began here in the latter half of the 19th century, as the astonishing jumble of bones that would be preserved at Dinosaur National Monument came to light. More than a century later, the quarrying at the main site at Dinosaur has been halted in favor of even richer finds elsewhere in the park. Today, pipeline crews crossing the Uinta Basin routinely find fossil sites as they trench. The land holds many undiscovered secrets and treasures.

The youngest layers in this cake, the flame-colored lake sediments of Bryce and Cedar Breaks, are less than 65 million years old.

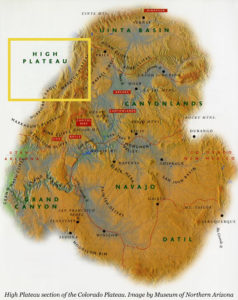

High Plateau Section

As we make our last great sweep to the west and approach the edge of the Wasatch Plateau in central Utah, the High Plateau section comes into view. This is the highest part of the region, where long forested plateaus are laid out beneath us, parallel splinters of land separated by a series of faults that angle roughly north to south. Stretched beyond its limit tens of millions of years ago, the earth’s crust split and broke into elongate slices that were uplifted and tilted into the High Plateaus of the southwestern Colorado Plateau. Their southern end consists of four escarpments that begin near Kanab, Utah, and climb like steps to the north—the Vermilion, White, Grey, and Pink Cliffs: the Colorado Plateau’s Grand Staircase.

Flying north from the deeply incised cliffs n ear Fredonia, we are moving forward in time, covering millions of years in just a few miles. The youngest layers in this cake, the flame-colored lake sediments of Bryce Canyon National Park and Cedar Breaks National Monument, are less than 65 million years old. Imagine each of these grandstand steps extends south to cover even the Grand Canyon, and you can see what erosion has removed in the last few millions of years. The strange hoodoos and goblin shapes of the soft lake sediments of Bryce Canyon and Cedar Breaks are testimony to continuing erosion, the same processes that sculpted the massive domes and kingly thrones of Zion National Park’s gleaming white Navajo Sandstone.

ear Fredonia, we are moving forward in time, covering millions of years in just a few miles. The youngest layers in this cake, the flame-colored lake sediments of Bryce Canyon National Park and Cedar Breaks National Monument, are less than 65 million years old. Imagine each of these grandstand steps extends south to cover even the Grand Canyon, and you can see what erosion has removed in the last few millions of years. The strange hoodoos and goblin shapes of the soft lake sediments of Bryce Canyon and Cedar Breaks are testimony to continuing erosion, the same processes that sculpted the massive domes and kingly thrones of Zion National Park’s gleaming white Navajo Sandstone.

Perhaps more than in any other portion of the Colorado Plateau, this feels like another world. Here there are deep forests and high snows; it feels less like the arid Southwest with its slickrock and painted badlands than like the high mountains of Montana or Colorado. Deep snowfall here in the winter provides water to the streams which eventually join to form the great canyon-cutting rivers. It somehow does not seem surprising that a Columbian mammoth skeleton was discovered on the Wasatch Plateau, at the extreme western edge of the High Plateau section. The old mammoth was out of his range, high up on the plateau’s side, and his old bones still contained preserved collagen, even after 11,000 years. There are places in the High Plateau section where it would hardly be surprising to see an Ice Age dire wolf running in the snowy forests or camels and mammoths grazing on the wide grasslands.

The great faults that separate plateau from plateau have been conduits for many things over the millennia. Millions of years ago, they served as pathways to the surface for molten magma. Brian Head’s volcanic rocks cap the Markagunt Plateau, while farther east lava flowed out over the land less than 2 million years ago. In historic times the tide of Mormon settlement washed south from Salt Lake City, following the valleys eroded along these same faults. Tiny towns sprouted at the bases of the plateaus—watered by mountain streams and rich in fertile bottomlands, they became important agricultural centers until the agricultural depression of the 1920’s and the routing of the main transportation and shipping arteries left them isolated. These faults are also seismically active, and earthquakes regularly rock the torn landscape of the Plateau’s western edge.

This section of the Colorado Plateau is a study in contrasts: red rocks and green pines, snow and sand, high plateau and deep valley. Even the attitudes of the people towards their land illustrate such contrasts. Local Paiute Indians once held that the glorious white-walled canyon of the Virgin River was an evil place because the sun never shone deep in its side canyons. They refused to guide early travelers into it, preferring instead to remain outside the entrance while others explored. Mormon settler Isaac Behunin nonetheless built a cabin there in 1862; to him the canyon was so reminiscent of glory and the spires of Heaven that he named it Zion. Today, the valley called Zion is revered as Utah’s oldest national park.

What the future brings for this landscape millions of years in the making, and how we will keep all the pieces together in a way that is healthy both for the land and its natural and human communities remains to be seen.

Alighting again on earth after our journey over the Plateau, I reflect on what we have seen. The landscapes of the Colorado Plateau are a diverse pallet with the unique individual character of each region born of its own geology, geography, topography, and climate. These landscapes have been shaped for millions of years, and are only the most recent expressions of a continuing complex interaction of water and wind with powerful forces deep within the earth. These lands have in turn shaped and molded the people who have come to explore, traverse, and settle here. Often those who came left quickly due to the overwhelming geography. Those who stayed would come to mirror the landscape itself after a time: rough, stubborn, isolated, and independent. Mountains and canyons and aridity have helped shape borders and policies, shapes that are with us even in our modernity.

The landscapes of the Plateau are many things to many people. To earth scientists, they are places to study the processes of the land, laid bare as a geological spectacle. To biologists, they provide for the study of arid land communities and survival in a region of little moisture and much rock. To the artist and poet, the landscapes are places for inspiration, where the bones of the earth are exposed in an impossible fanfare of light, color, and form.

To others, the lands of the Colorado Plateau provide a challenge; they are places to reclaim from the “uncaring” hand of nature for the good of people. Human hands have already created many new landforms. Blue lakes lie strangely out of place in the stark and tumbled terrain. Green fields appear like jewels amid the red rocks, and deep pits and pipes reach into the depths of the mesas for minerals born millions of years ago. Already scant rivers are sent far away to growing cities elsewhere, allocated so that their waters are not technically or legally available for the biological communities of the lands across which they flow.

What the future brings for this landscape millions of years in the making, and how we will keep all the pieces together in a way that is healthy both for the land and its natural and human communities remains to be seen. But after this flight of fancy around the Colorado Plateau, I realize that it is this all-encompassing vision that is perhaps the most important for us to have. For after the exploration, the science, and the politics, it may well be that only through the eyes of the birds can we see enough about this mosaic to learn how to protect and preserve it in all its uniqueness.

The Shape of the Land was originally published in Plateau Journal, Spring/Summer 2002, by the Museum of Northern Arizona.

Republish

Republish Our Content

Corner Post's work is available under a Creative Commons License and under our guidelines:

- You are free to republish the text of this article both online and in print (Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence as in most cases we are not the copyright owner) but:

- you can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style and ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on Corner Post;

- if you’re republishing online, you have to link to us and include all of the links in the story;

- you can’t sell our material separately;

- it’s fine to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories;

- you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories to be republished individually;

- you have to credit us, ideally in the byline; we prefer “Author Name, Corner Post,” with a link to our homepage or the article; and

- you have to tag our work with an editor’s note, as in “Corner Post is an independent, nonprofit news organization. See cornerpost.org for more.” Please, include a link to our site and our logo. Download our logo here.

Christa Sadler has called the Colorado Plateau home for more than three decades. She holds a Master’s Degree in earth sciences and paleontology from Northern Arizona University, and a bachelor’s degree in physical anthropology from the University of California at Berkeley.

Christa has been fortunate enough to be a writer, researcher, teacher, and wilderness and river guide throughout the region since 1988, and for her there is no greater love than these landscapes. Her articles and photographs have appeared in Earth Magazine, Plateau Magazine, Plateau Journal, Sedona Magazine, and Sojourns. She is the editor and publisher of There’s This River…Grand Canyon Boatman Stories, and the author of Life in Stone: Fossils of the Colorado Plateau, Dawn of the Dinosaurs: The Late Triassic in the American Southwest, Where Dinosaurs Roamed: Lost Worlds of Utah’s Grand Staircase, and The Colorado.